DR. NEWTON’S HEALING MEDIUMSHIP.

Extracted in part from issues of the “The Spiritualist” 1870.

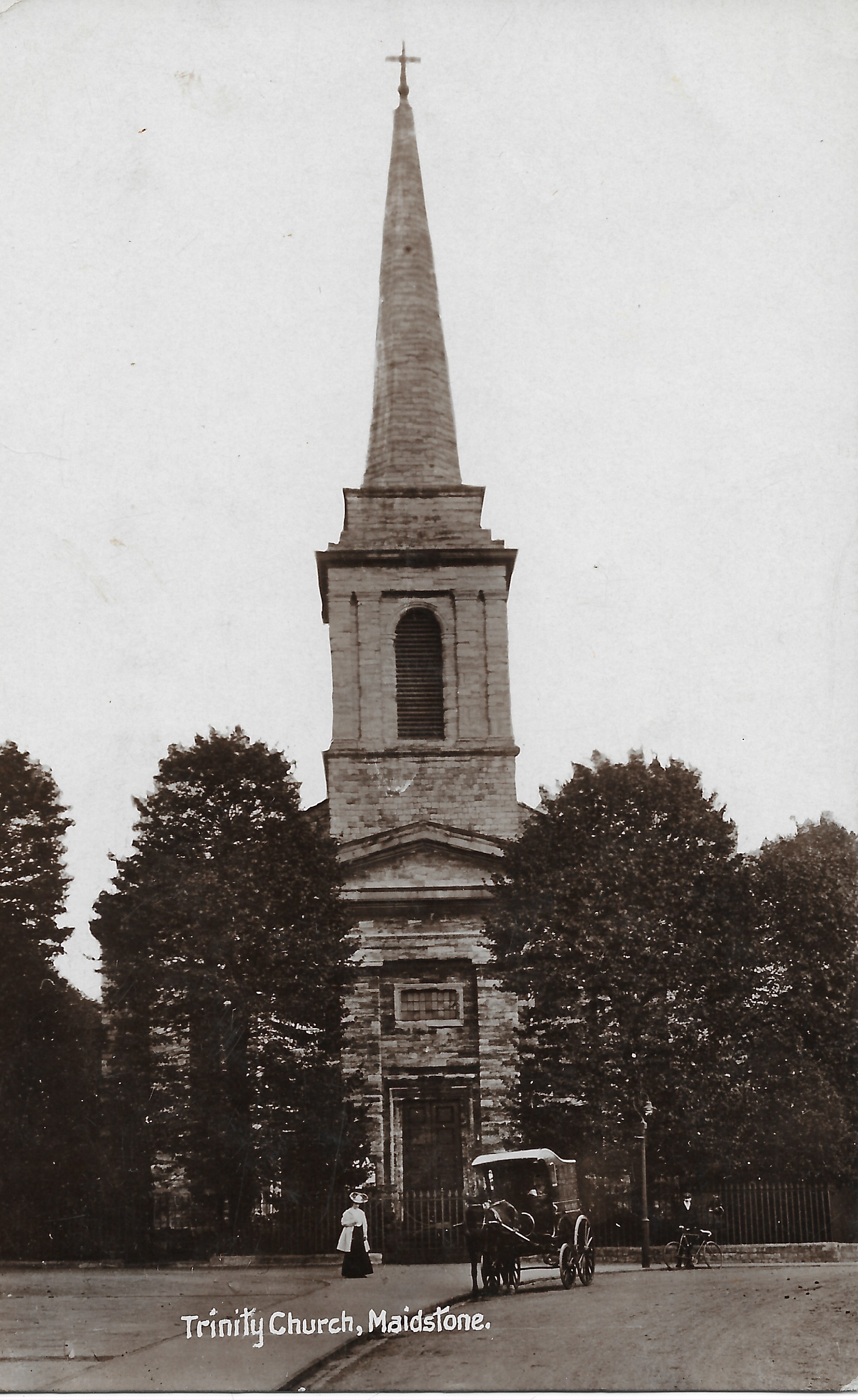

Since the issue of the last number of this journal, Dr. Newton has paid Sunday visits to Andover, Maidstone, Birmingham, and Kingston-on-Thames. He will remain in England till the middle of September, when he leaves for Rome and Jerusalem, in both of which places he intends to heal the sick poor, without charge, as usual. We have received the following particulars about Dr. Newton’s visit to Maidstone, where he was very successful, partly in consequence of the excellent arrangements, the names and addresses of the invalids being all taken, and the observers being admitted by tickets, and placed where they could look on but not interrupt :

To the Editor of the Spiritualist.

SIR, —Having been present at the reception of Dr. Newton on his arrival in London, and having then subsequently witnessed several striking cures, and received benefit also myself, I felt desirous to secure his powerful influence for several of my own suffering friends, as well as for the afflicted of this town and neighbourhood in general. I invited him to spend one of his Sundays at my house, to which he kindly assented, fixing the 24th July. He arrived the previous evening, and commenced his healing efforts before ten on Sunday, working hard until nearly one o’clock, during which space of time he treated fully 180 invalids, being an average of one to a minute, besides finding time occasionally to address those present in several short and stirring speeches.

I had prepared and covered a large yard and coach house, capable of accommodating more than 500 persons, and I suppose 300 may have been present. Great harmony prevailed, and all appeared deeply interested in the novel proceedings, and, at the close, a hearty vote of thanks was accorded to me. Dr. Newton expressed himself highly satisfied, and stated that he felt the conditions were more than usually favourable for the successful exercise of his great gift.

I find the Doctor’s remarks were received very differently, according to the varying state of mind of his hearers, some were sorely offended at his profession of personal purity, or freedom from sin, and which he stated was needful for the effectual and proper exercise of the gift of healing. Others took umbrage at his denial of the exceptional Divinity of Christ, and his attempt to account for his so-called miracles in a way consistent with the laws of nature as exemplified in the science of psychology. Still, I believe not a few felt a true sympathy for the Doctor’s views, and the evident honesty and enthusiastic earnestness which animated him in all he said and did, could no fail to produce a good effect, and to insure respectful attention even from those who widely differed from him. I think it is best that the Doctor’s observations should follow, and not precede or accompany the healing, for I fancied I could perceive a decided diminution of power after he had finished an address, probably arising from a feeling of opposition in some portion of the audience, or possibly from a partial exhaustion through the effort of speaking. As to the cures effected on this occasion, I am not yet prepared to report fully, as I purposely allowed some time to elapse before I began to make inquiry, except so far as to question each patient immediately after leaving the Doctor’s hands. I give you the following cases, however, which have just been investigated, and may be fully relied upon, and I hope to be ready for your next issue with a more complete statement.

THOMAS GRANT. Shirley House, Maidstone, 10th August, 1870.

Thomas Grant was the maker of Kent’s best morella cherry brandy and he lived at Shirley House which was situated next to the factory in Maidstone.

(The “Spiritualist” explains that in the June number of the SPIRITUALIST, were 105 cases of cure by Dr. Newton with full names and addresses; in the July number 11 of these cases were shown not to be reliable, reducing the number to 94. Therefore Mr. Grant’s list begins with number 95. Of course, in a country town like Maidstone, where everybody knows everybody else, the reality of the relief given must be indisputable!)

95.* Mark Antony Twort, photographer, age 41. Great sufferer from indigestion for 6 years, causing a dull heavy pain about the heart. Dr. Newton called it heart disease, and promised to cure him, but for seven days after he saw the Doctor he was much worse, when, as he states, something seemed to drop or break away from the neighbourhood of the heart, and since that time he has been better than for years past. He thinks something has been forming internally for some years, and now seems to be gone entirely. He appears very grateful and talks of writing a letter of thanks to Dr. Newton. 96. Mrs. Martin, Wharf-lane, is grateful for benefit received. Rheumatic pains in hips disturbing her rest. Has now lost all pain, except a slight pain in the knee; sleeps well, and is wonderfully better.

97. Samuel Twiner Smither, 80, Union-street, age 22, deaf eight or nine years. Saw his mother, who states he can hear much better, as a proof she mentioned that in the night he was alarmed at a slight noise in his room made by a cat playing with a piece of newspaper.

98. John Dyer, Mill-lane, age 61. Great sufferer, and lame from rheumatics. Very much better. Walks without a stick, and can put his hand up to his head, which he has not been able to do for a long time.

99. William Ayres, Hart-street, age 43. Leg was broken about eight years ago, and until he saw Dr. Newton he had not been able to bend it; he can do so now, and put his foot to the ground.

100. Thos. Simmonds, builder, age 59. Has been seriously disabled and pained four and a half years, by what his doctors described as a loose piece of cartilage under the cap of the knee, causing the joint to be frequently upset by anything striking the inner side of the foot, notwithstanding that he always wore a laced elastic bandage, which he dare not leave off for an instant. He has consulted several doctors who have tried to move the joint in various ways, and a serious operation was proposed, but he was advised not to consent to it. Dr. Newton pressed the sides of the knee cap, and instantly removed the impediment; he ordered the bandage to be removed, and the knee has remained perfectly sound ever since. This important cure was both instantaneous and complete, and the patient is most grateful. 101. Mrs. G-, age 67, had suffered from stiffness, pain and weakness of one knee, which for several years had been gradually getting worse, and threatened to become quite a stiff joint. Dr. Newton’s touch caused a snapping sound, and instantly restored freedom to the joint, which has continued, and it is daily gaining strength.

102. Thomas Capon, St. Peter’s-street, age 68, fell from a ladder three years ago and injured his left leg, which he could only move by help of his hands. When Dr. Newton touched him he felt something give way under the knee, which he has since been able to move without using any assistance, and he is decidedly better and stronger.

103. W. R. Waters, 7, Charlton-street, New Brompton, Kent, age 29. Injury to the spine eighteen months since. Writes that he is very much better than he ever expected to be and can now attend to his business all day without being obliged to go to bed, indeed, he says, “I have every reason to believe what the Doctor told me is true–‘ You are well! you are cured!’

“The Spiritualist” of 15th June 1870 gives some details of the mysterious Dr Newton!

“DR. NEWTON’S HEALING MEDIUMSHIP. DR. J. R. NEWTON, the healing medium, was born in Newport, Rhode Island, United States, September 8th, 1810, consequently he is now about sixty years of age, and it was eleven years and a half ago when he first began to devote the whole of his time to the healing of the sick. In his lifetime he has passed through many changes and sorrows and has both made and lost several fortunes. He has often been in great danger of losing his life. When he was eight years old, a playmate gave him a push one day as he was whittling with a knife; he fell, and the blade of the knife went into his breast right up to the handle, but he recovered from the effects of this accident. At the age of ten he fell from a tree and was so much injured that his lower limbs were paralysed, and he could only draw himself along the ground by his arms; he recovered from this state in a single night, he believes in consequence of the healing ministrations of his unseen friends, the spirits. When about eighteen years of age he fell from the masthead of a vessel, but he was caught in the rigging, near the deck. At the age of nineteen, he, with seven other sailors, was out at sea upon a wreck for thirty-six days, yet they were saved. Since he has worked as a healing medium, he has often been in danger from mobs in different cities in America, before Spiritualism began to be understood there, and once at Havana in Cuba, the crowds were so large, and some among the people so antagonistic, that a file of soldiers was brought out to keep order.

Now as to his method of working. A few friends keep a clear space near him as well as they can, and one by one those who are afflicted come under his hands; he finishes off most cases in one or two minutes, but some of them require his attention for five or more minutes. He talks little, but lays his hands on the afflicted parts, sometimes with a short invocation, something like this—” May the Almighty Father and His holy angels pour out their love upon this afflicted one and remove his disease from him. Be healed! You are well!” When a person comes up to him, in many cases without the interchange of a word, he lays his hands on the seat of the disease, and says what is the matter; he also tells some of them at once that they are incurable; others, he remarks, he can cure at once, and he tells some that he will partially relieve them at once, but that they will be well within a given number of days. Some come up to him, and he does not know what is the matter with them, but asks them the nature of their complaint. Others consult him about sick friends at a distance, and in some cases he suddenly stops the speaker, and accurately describes to him or her the sick friend. With respect to the clairvoyant powers already mentioned, which are occasionally exhibited by Dr. Newton, in one instance at the Cambridge Hall, he said :—” Your sick friend has a yellow sallow complexion, as if he had had the jaundice, and he has bushy black whiskers; I dare say you wonder how I know this, and I can hardly tell you myself, but I see him by a kind of clairvoyance, reflected, I suppose, from some image in your brain.”

In one instance, a little boy, rolled up like a ball in his mother’s arms, and having an idiotic expression of face, was brought under the notice of the healer. Dr. Newton at once remarked ” This child is what in old times was called possessed by devils, but I will drive away the evil influences so that they shall annoy him no more.” He then made some passes over the child, whose limbs then slowly extended themselves, until at last they stood out straight. Dr. Newton then took his hands, and said, “Come now, walk my little darling,” but although the legs were straight, they doubled up at the knees, in consequence of weakness there, and the child not knowing how to walk. Dr. Newton told his mother to take him home, to apply water as hot as he could bear it once a day to his back, and added that in a few days the boy would be quite well, and must be taught to walk.

Dr. Newton is a man of action and of few words, and it is only now and then, while doing his work, that he makes a few remarks. In those remarks he often stated that love is a positive substance, and that it is in consequence of the love which he bears to all mankind, that the spirits have the power to enable him to effect his marvellous cures; he also states that the love of those he has cured, as well as of others, strengthens his healing powers wherever he may be. He cannot cure anybody who comes to him in a state of mind antagonistic to him and his work. He says that a great number of bright and glorious spirits are helping; him in his work, and that among them is Jesus Himself, who like the others is progressing in love and wisdom, and says that were He to return to earth-life again with His present knowledge, He would never use such harsh words as ” 0 generation of vipers!” to any of His fellow creatures!